Authors note: This article was co-written by Meghan Odsliv Bratkovich, and was submitted for publication to the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics research journal.

How students have been taught mathematics has changed over time. Algorithmic computation and formulaic memorization have largely given way to divergent thinking and emphasis on mathematical understanding. The Common Core State Standards both reflect and guide corresponding shifts in the field of mathematics and in mathematics teaching, emphasizing communication, argumentation, and reasoning skills that are essential for college and career readiness. Despite this, even highly successful teachers often lack the time and space necessary to make sense of what this means and ways it might positively affect their practice–how students are expected to express, construct, and represent mathematical sense, how teachers are expected to make sense of mathematics for their students, and how teachers’ engagement in systematic sensemaking through inquiry can facilitate this process.

The interconnected considerations incorporated in Practice Standard 3 are integral to the construction, communication, and critiques of viable arguments in mathematics (e.g., appropriate processes, structures, proofs, formats, logic, and terms). Even very knowledgeable and highly effective teachers can leave these underlying strands of argumentation snarled between and knotted up in correct and incorrect solutions, sufficient and insufficient evidence, long and short answers, or clear and unclear writing. Unfortunately, this frequently places the burden on students to disentangle the ambiguous, vague, and unspoken, yet structured language and logic of the discipline. Students must often master these language-laden mathematical practices through trial and error, all the while developing conceptual understanding, evaluating arguments placed before them, and attempting to craft viable mathematical arguments of their own.

The Common Core State Standards describe mathematically proficient students as those who are capable of “breaking [situations] into cases,” and able to “build a logical progression of statements,” and “justify their conclusions [and] communicate them to others” (CCSS.Math.Practice.MP3). Developing this student proficiency can be facilitated when teachers actively engage in the same types of systematic sensemaking they expect of their students. By similarly inquiring into their practice as math teachers, these teacher researchers can break down mathematical practices, build pedagogical practices that purposefully attend to mathematical content and expectations held by the field, and justify and communicate their conclusions to students, colleagues, teacher educators, and other stakeholders.

This article traces one practitioner’s sensemaking around viable arguments from two perspectives–a high school mathematics teacher (Andrew Paulsen) and a university-based researcher (Meghan Odsliv Bratkovich). To organize this discussion, the following sections each speak to one facet of knowledge for, in, and of practice (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999, p. 250). In the knowledge-for-practice section, I (Meghan, university researcher) break down the sensemaking process by which Andrew enhanced his understanding of mathematical argumentation. In the knowledge-in-practice section, we speak jointly about how making sense of unnoticed aspects of mathematical reasoning reconstructed our understanding of content. Building this more refined understanding of what mathematical reasoning involved catalyzed changes to Andrew’s teaching practice that purposefully attended to the previously-unseen language expectations central to determining argument viability. In the final section, I (Andrew, practitioner researcher), communicate a vision of knowledge-of-practice that invites other teachers to engage in similar collaborative, multilayered sensemaking.

Knowledge-for-practice

Sensing that his ninth-grade, Algebra I students seemed to ‘understand the math,’ yet struggle to craft arguments he could see as ‘effective,’ ‘clear,’ or ‘viable,’ Mr. Paulsen (as he is known to his students) began to question what he could do to help students meet Mathematical Practice 3. Revisiting previous arguments that he used in class as exemplar models, I challenged him to figure out and name what it was specifically that made him view them as ‘effective,’ ‘clear,’ or ‘viable’, (as opposed to ‘right,’ ‘accurate,’ or ‘correct,’) in the first place. This led to an ‘aha’ moment about what it means to ‘understand math’ that eventually led Mr. Paulsen to three takeaways: deeper awareness of his own expectations, new perspectives on his content, and growing appreciation of the importance of attending to how sense is constructed and conveyed in mathematics.

Mr. Paulsen had always held expectations for argument clarity. However, he selected exemplars based on how convincing or moving they were to him and had never unpacked the components and criteria that led him to judge them as clear or unclear. He expected arguments to meet a tacit threshold for clarity, much like Supreme Court Justice Stewart, who famously did not attempt to define his threshold for obscenity, instead stating “I know it when I see it” (Jacobellis v. Ohio, 1964). He essentially held up arguments with the hope that his students would be able to intuitively sense why they were clear—what made each exemplar exemplary.

To move beyond this, I encouraged Mr. Paulsen to apply similar systematic reasoning skills to those he teaches, aiming to explicitly define his de facto ‘know-it-when-I-see-it’ criteria for clarity. Guided by little more than my simple questions such as ‘what about this part makes it clear?’ he identified discursive patterns between and within his exemplars. He noticed how sentences built on one another and played specific roles within each argument, and for the first time realized his implicit reliance upon mathematical language structures when evaluating argument clarity.

Mr. Paulsen deduced that his exemplars often follow an answer-definition-example structure where a claim is made, a mathematical rule is stated, and an explanation linking claim to rule is offered. This parallels the Toulmin ‘claim-evidence-warrant’ structure common to many disciplines, and recently adopted by other departments at Mr. Paulsen’s school. He also found that exemplars were less reliant upon mathematical terminology like multiples, domain, and functionthan anticipated, and surprisingly, that some ‘everyday’ words (e.g., must, any, since, because) strongly influenced argument clarity.

This noticing of mathematical language, however, does not imply that expertise in linguistics or English Language Arts is necessary, though mathematics teachers often view language as outside their content (Harper & de Jong, 2009). On the contrary, Mr. Paulsen’s sensemaking process highlights the sophisticated language expectations teachers already hold and reveals unseen expertise in the language of mathematics. Many aspects of mathematics, such as the argumentation discussed here, simultaneously require discipline-specific structures, patterns, and word usage. Therefore, socializing students into these mathematical discourse practices (Moschkovich, 2007) falls under the purview of mathematics teachers because it is not the teaching of language, but the teaching of mathematics.

Mr. Paulsen’s efforts invite other practitioners to undergo their own sensemaking process and seek their own ‘aha’ moments. This process positions teachers to notice the overlooked language of mathematics, see their own language expertise, and reveal unseen facets of their existing content knowledge. This sensemaking empowers teachers to see themselves as those best equipped to sense, make sense of, and become sensitive to the language of mathematics.

Knowledge-in-practice

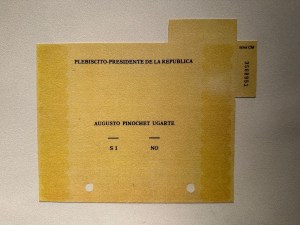

Once Mr. Paulsen felt he had a better handle on how mathematical sense was made and constructed, we considered how this information could be used to give more meaningful instruction and formative assessment to his students. Instead of planning to simply show another exemplar argument, we chose to create and juxtapose two different arguments for his students to discuss in class. Using language inspired by multiple student work samples, we created two viable arguments for an adapted MARS Task (Toy Trains) his class had recently completed (see image below).

Maria says that a train set from Julio’s Puzzles has 40 wheels. Can Maria be correct?

|

A:

|

B:

|

| Maria is correct because Julio’s Puzzles only sells trains with exactly 8 wheels. In the real world, stores only sell full train sets. This means that any train sets Julio sells must be sold in multiples of 8. In this example, Maria claims to have a train set with exactly 40 wheels. Since 40 is a multiple of 8, Maria is correct. |

Maria is correct that she says a train set from Julio’s Puzzles has 40 wheels. Maria must buy a plethora of train sets. Trains from Julio’s Puzzles do not necessitate an engine, unlike Alex’s Toy Shop. Therefore, Maria’s argument is affirmed, and she will be able to obtain a train set from Julio’s puzzles that has 40 wheels. |

Mr. Paulsen’s goal was to draw on his own knowledge and sensemaking of mathematical argumentation to push his students to notice and focus on the overall structure and discourse-level features of a viable argument in mathematics rather than the word- and sentence-level features that both he and his students had focused on in the past. Knowing that his students tended to regurgitate phrases in the question and fish for vocabulary, we crafted Argument B to use many of the “big words” and question re-phrasings that the students associated with good answers, but contain little logical structure.

We were careful to use the word mustin both arguments to show how a word can contribute to mathematical reasoning in one case (Argument A), but not another (Argument B), and was careful to make each argument of approximately equal length to avoid another common student misconception that better arguments were simply longer. Argument A used more simplistic words, but included a claim, a statement of mathematical base case or universal truth, and how the specific case related to the base case. In short, it used the internally cohesive structure consistent with a viable mathematical argument that Mr. Paulsen had previously identified.

The class on creating viable arguments opened with a Do Now we created in which the students were asked to reflect on what it means to “construct a viable argument” and to identify the structural components of a viable argument in English class. This was intended to focus the students on reasoning and to link the structure of mathematical argumentation with a similar claim-evidence-warrant structure the students were familiar with from ELA.

Mr. Paulsen then presented the structure of a viable argument to the class, mapping his own sensemaking onto the claim-evidence-warrant structure used throughout the school. Narrating a smartboard slide, Mr. Paulsen described a claim as the answer to the question, evidence as a universal truth, and a warrant to show how the specific case is an example of the evidence. He then guided students through a sample argument, focusing specifically on the new and unfamiliar component of a universal truth by using a comfortable and familiar example–that all even numbers were divisible by two.

After leading a discussion about this straightforward example, students were then given the two Toy Train arguments we had created. In addition to comparing and contrasting Argument A and B, the students were asked to identify the components of each argument and make a conjecture about which argument they thought a college student would use.

As expected, the students initially focused on specific words they associated with academic writing, such as the words ‘plethora,’ ‘necessitate,’ and affirmed,’ but the class soon realized that “fancy vocabulary” did not necessarily equate to a “viable argument.” However, Mr. Paulsen did draw students’ attention to certain specific words, namely since, which signaled the base case was the reason that the specific case was true. He emphasized how sinceshowed the causality between the evidence and warrant in a way that and, a transition word commonly used by the students, did not.

Importantly, though Mr. Paulsen provided a structure for argumentation and attended to specific words, he was careful not to turn the writing of mathematical arguments into a prescribed procedure. He repeatedly pointed out multiple ways an idea could be expressed and challenged students to provide different word choices as the class co-constructed viable arguments.

By the end of the class, most students were able to choose Argument A as the more viable option, and identify the claim, base case (evidence), and specific case (warrant) within Argument A. Thoughmany students still tended to describe Argument A using the same vague language often used by teachers (it needed to “be clearer” or “elaborate more”), some students were able to express specific ways that both Argument A and their own arguments could be improved to better mirror the structure and viability of Argument B.

Knowledge-of-practice

What began as an attempt to create an intervention for my students to make sense of constructing viable arguments quickly revealed the need to better understand my own sensemaking. My advice to students to “show your thinking,” “say how you got there,” or “be clear” did not provide sufficient scaffold for students to be able to craft a viable argument.

After Meghan asked me to reflect on what it means to ‘be clear,’ I recognized that I needed to dig deeper and unpack my own knowledge and expectations about the argumentation process that I had taken for granted in my practice. I shifted from evaluating the arguments my students were producing to systematically reasoning through my own mathematical understanding and expectations for arguments. By engaging in this process, I could see my own expectations more clearly and was able to articulate what I had been pushing my students to do. I then worked with Meghan to develop a modified claim-evidence-warrant structure to scaffold arguments for my students and guide my student feedback to be more meaningful, specific, and actionable.

Though Meghan’s questions prompted this journey, her asking about clarity led me to my own questioning about mathematical reasoning. I am now more cognizant that my previous instruction was only sufficient for students who could adequately guess what I meant when I told them to “be clear.” This process of inquiry helped me peel back the layers of mathematical expectations for argumentation and scaffold students beyond the sentence or vocab level so that they can make arguments at the discourse level.

The process of sensemaking was just as important as the product of the intervention. In other words, instead of jumping over the process (my inquiry) to get to the product (the intervention), it is just as important to focus on the sense-making process. The intervention we produced met my intent to better prepare each of my students to access Mathematical Practice 3, but that was not the only valuable takeaway. As a teacher and lifelong learner, engaging in this inquiry not only prepared me to better understand one concept or teach one topic; it prepared me to go back and investigate any mathematical practice (such as what it means to “attend to precision”), which motivated me to share this sensemaking process with other teachers. In the same way that Meghan’s inquiry kick-started the reflection on my teaching practice, I hope that this research can model and scaffold sensemaking in a way that can support other math teachers trying to come to a better sense of their own mathematical expectations, assumptions, and practices.

References

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. Review of Research in Education, 24, 249-306.

Moschkovich, J. N. (2007). Examining mathematical discourse practices. For The Learning of Mathematics, 27(1), 24-30.

Harper, C. A., & de Jong, E. J. (2009). English language teacher expertise: the elephant in the room. Language and Education,23(2), 137–151.

Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964)